Coffee Talk with Samadhi Lipari: Renewable energy expansion in the Simeto valley

Join us for a coffee chat with Samadhi Lipari, a geographer and researcher at the University of Catania (UNICT). In BIOTraCes he contributes to the case study on “Simeto River Alliance for Biodiversity” about grassroots groups who fight for ecological recovery and protection of the Simeto River on Sicily. Samadhi´s specific focus within this research is on photovoltaic energy production in the River valley.

What is the focus of your research on the Simeto River?

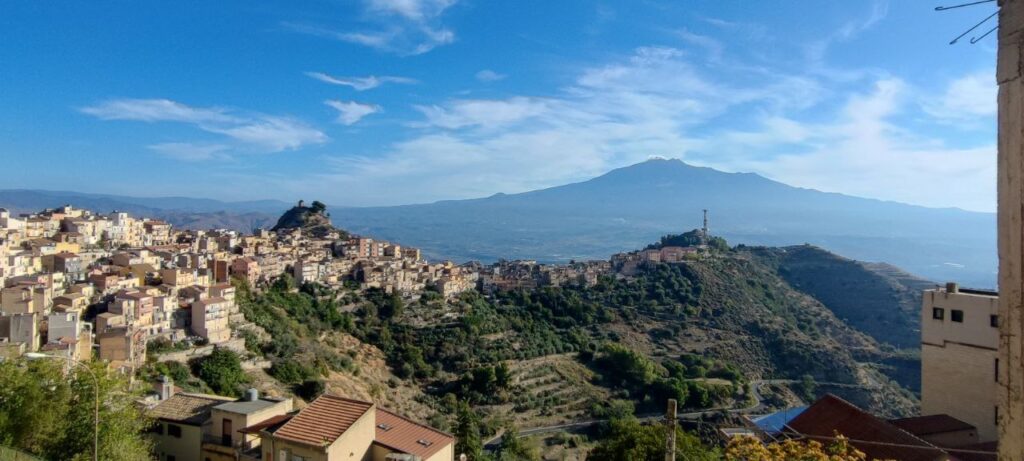

Our team at UNICT is conducting research on the Simeto river, the largest river of Sicily. The river originates from the Nebrodi mountain range in the north, which is part of the Apennines extending down from northern Italy. Flowing southward from the northern coast of Sicily, the Simeto River borders Mount Etna. We are studying the river through a relational framework that connects three key elements: energy, water, and agriculture. Our research focuses on: (1) exploring innovative agricultural practices along the river, (2) examining the management of water resources, particularly for irrigation, and (3) investigating energy production in the valley, with an emphasis on electricity generation. My specific focus within this research is on energy production.

What is happening regarding renewable energy production in the Simeto valley?

I am focusing on photovoltaic energy and the emerging sector of “agrophotovoltaics,” an innovative field being developed in a “backward” area. The expansion of renewable energy production in the Simeto Valley is closely linked to agriculture in several ways. Historically, the Simeto Valley was once covered by forests before being cleared for wheat and orange farming, which became its primary agricultural focus for centuries. However, the agricultural sector is now in crisis due to climate change and long-standing structural shifts.

We are currently seeing a wave of large land acquisitions for energy purposes, with significant investments in large-scale photovoltaic plants being built on what were once agricultural lands. A significant portion of these plants are “dual-use”- agrophotovoltaic systems that – produce energy while some form of agricultural activity continues. However, even this model presents contradictions and challenges, particularly in terms of land use and ecological impact. For instance, the Valley’s traditional citrus monoculture, once the area’s staple crop, is being replaced by energy plants. It is as if we are observing a shift from a citrus monoculture to a silicon monoculture.

“It is as if we are observing a shift from a citrus monoculture to a silicon monoculture.”

Are photovoltaic plants a problem in themselves?

The technology itself is not the issue – renewable energy is essential, as the climate crisis is real. However, the governance of the energy transition has been highly problematic in rural areas, often resulting in unintended consequences. This is a difficult concept to convey to climate justice movements in urban areas. While the need for renewable energy is clear, its implementation in rural regions is far more complex than it might seem.

Who is developing renewable energy plants in the Simeto valley?

The renewable energy plants in the Simeto Valley are being developed by large corporations. For instance, Amazon owns several plants in Sicily, including one in the Simeto Valley with a capacity of around 60 MW, which occupies many hectares of land, and another in western Sicily. While these big corporations play a crucial role – particularly through their power purchase agreements, which are replacing national subsidies for green energy that have decreased over the past decade – there is a concern. The risk is that dual-use photovoltaic plants are being leveraged by these corporations without paying too much attention to agriculture. Rather, farming seems leveraged as a “Trojan horse” to gain control over Sicily’s inland lands and produce cheap solar energy, useful also to green their reputation. Therefore, I believe the situation in the Simeto Valley highlights the crucial role local authorities must play in engaging local communities and initiating a conversation about the impacts of large-scale energy projects on the local environment and society. This is not an issue that can be effectively managed from capital cities or corporate offices far removed from the area.

What impact does the construction of renewable energy plants have on less developed or rural areas?

In less developed areas, we are seeing a wave of investment in renewable energy, exacerbating these regions’ role as energy exporters. As a result, these rural areas are increasingly being converted into industrial areas. Renewable energy, therefore, plays a significant role in driving long-term changes in these areas. This shift has profound effects on both the socio-economic fabric and the biodiversity of these regions.

“Rural areas are increasingly being converted into industrial areas.”

What is the effect of photovoltaic plants on biodiversity in the Simeto valley?

The relationship with biodiversity is complex. On one hand, the crisis in agriculture and the resulting loss of biodiversity by climate change has paved the way for large industrial photovoltaic plants to be built. Local farmers often view the loss of biodiversity as a cause rather than an effect of these developments. Had the agricultural sector remained viable, the influx of large investments from international corporations into Sicily might not have occurred. However, this argument is not without its complexities. While the citrus monoculture previously practiced was not healthy for the soils, it is also true that high-quality citrus crops are now being lost, as areas once devoted to these crops are now occupied by photovoltaic plants.

The law requires that a crop plan be implemented when building a dual-use plant. However, these crop plans are often created simply to meet legal requirements. As a result, non-native crops—often referred to as “alien” crops—are often chosen. These are easier to grow under solar panels, with lavender being a popular example. There is now an abundance of lavender in these areas, but it does not contribute to the local ecosystem in the same way that native crops once did.

What local socioeconomic challenges arise from the construction of renewable energy plants?

One risk is “green grabbing.” As I mentioned, agriculture is in crisis, and many farmers are struggling to find additional sources of income or are even looking to sell land that has become a financial burden due to low productivity. Meanwhile, the highly subsidized renewable energy sector is in desperate need of large land extensions. This creates a perfect match between supply and demand.

However, this occurs in a context of weak territorial planning, where permitting procedures and regulatory frameworks are highly centralized. Local municipalities or stakeholders have little to no involvement in the zoning and approval processes for these projects. As a result, rural areas are being transformed into industrial energy hubs in a disorganized manner, with local communities having little influence on the development of energy plants. There is no real participation or imagination about what their territory could become in the future.

“There is no real participation or imagination from local stakeholders about what their territory could become in the future.”

What do local stakeholders need to have more say in decision-making?

First, they need access to information about where the renewable energy plants are located. This is crucial for a couple of reasons. Having the right information makes it easier for local authorities, such as municipalities, to issue permits and enables stakeholders to effectively communicate their concerns. In most of the cases we studied, the absence of a regional energy cadaster (database) undermined local communities and municipalities capacity to have a say in the designing and zoning of new plants. Second, and more challenging to address, is the need to reverse reforms made in the last decade that have shortened the windows of time during which stakeholders can provide feedback. Reforms aimed at ensuring local community participation need to be reinstalled to give these communities a role in the decision-making process.

How does your research help local stakeholders?

Our goal is to create a collaborative and critical map of photovoltaic plants in the Simeto Valley. We have been mapping their locations, identifying their owners, and tracking the land they occupy or will occupy. The UNICT team is working to overlay this basic information with data on local vegetable and animal species, and the cultural and historical heritage of the area.

Additionally, we are taking a forward-looking approach. We are organizing a series of workshops to engage local communities and gather input on how they envision the future of their territory. This adds a crucial layer of local perspective on how they want the land to evolve.

The transformation of rural agricultural land into an energy district often carries the narrative of “empty” or “backward” land—suggesting it is a suitable area for energy investment. This stigma implies that developing the land for energy purposes is a logical choice. However, it is essential to challenge the notion that the land is empty. There are communities here that want to have a voice, not necessarily to block these projects but to shape their design so that they can derive benefits. In some parts of the region, residents envision alternative uses for the land—such as a municipality planning a new city park as part of an urban regeneration effort. This reimagines the territory, even in areas designated for energy plants. The collaborative map helps visualize these ideas and challenge the “silicon monoculture” narrative.

“We are organizing a series of workshops to engage local communities and gather input on how they envision the future of their territory.”

What do you hope will be the transformative impact of your research on the area?

A strategy for triggering transformative change in the area is simply providing information and raising awareness. The goal is to trigger debate that encourages different stakeholders to actively participate in redesigning and reimagining their territory, and to better understand what is happening, as there is currently little widespread awareness. While people know something is happening, the scale of the phenomenon is not fully understood—sometimes not even by local officials. And the scale is enormous: tens of thousands of hectares are being transformed, with projects set to last for the next 20 to 30 years, a long-term horizon.

I hope to stimulate debate and foster collaborative mapping efforts, which could lead to tangible actions, such as reclaiming ownership or asserting the right to participate in the transformation of various areas. As for the scalability of the project, I believe it has the potential to extend beyond the Simeto Valley to other regions of Sicily, as the wave of renewable energy investment is affecting them as well. We have a view on creating a comprehensive map of Sicily’s energy transition, integrating all relevant layers of information. Ultimately, I hope my research can help raise local communities’ awareness, encouraging them to engage with their municipalities and take an active role in understanding and shaping the changes unfolding in their territories.